Imagine a city with an infrastructure problem (I know, it’s hard to imagine). The problem is this: Roads are breaking down faster than they can be repaired. As the city’s population grows, road workers cannot work fast enough to compensate for the additional traffic. Each road closure for repairs means more traffic on alternative routes and, therefore, even faster decline. Eventually, the few alternative routes that are open no longer connect to one another; construction crews can no longer get to the roads that need to be repaired; and ultimately, the system shuts down. Death by growth.

Imagine a city with an infrastructure problem (I know, it’s hard to imagine). The problem is this: Roads are breaking down faster than they can be repaired. As the city’s population grows, road workers cannot work fast enough to compensate for the additional traffic. Each road closure for repairs means more traffic on alternative routes and, therefore, even faster decline. Eventually, the few alternative routes that are open no longer connect to one another; construction crews can no longer get to the roads that need to be repaired; and ultimately, the system shuts down. Death by growth.

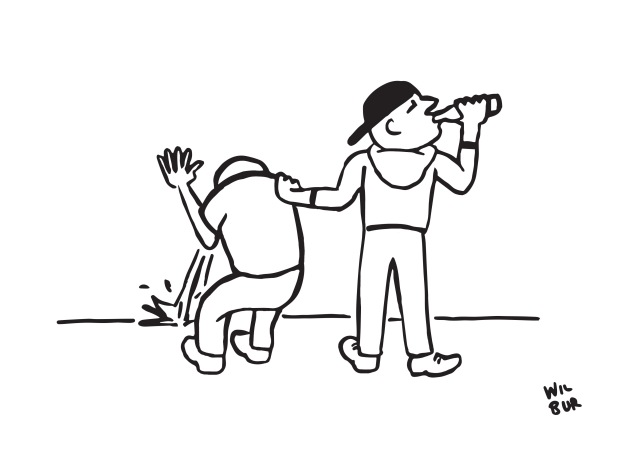

This is the basic idea behind the classic S-curve of growth (below), which is said to be so ubiquitous. From cities to cellular biology to Fortune 500 companies, most systems follow a similar pattern. They must balance between growth and maintenance.

Understanding which phase we’re in—whether high-growth, high-maintenance, or transition—can be advantageous. It can help extend the life cycle of our products, businesses, bodies, personal lives, and relationships. But when we refuse to acknowledge this shift, that’s when problems arise.

In business, this refusal is called the denial phase. As one Harvard Business Review article puts it, “[R]etailers often go through a long, painful period of denial before they acknowledge that growth has ended and it’s time to switch strategies. […] Consequently, they keep expanding until their chains begin to collapse under their own weight.” The article is referring to a study of 37 U.S. retailers—all with over $1 billion in revenue, all with top-line growth rates slowed to single digits. But while several of these historic giants were collapsing “under their own weight,” many had found a solution to the stagnation.

Companies like Macy’s, Home Depot, and McDonald’s have extended their lifespans by focusing on the maintenance phase. They thrive by creating efficiencies in their existing stores rather than opening new ones. In other words, they transitioned from a strategy for rapid growth to one of maintaining their large size.

This is not to say that growth is negative. Pure growth and pure maintenance are not what creates life. It is the in-between where we exist. As the Harvard Business Review authors explain, “this is a low-growth, not a no-growth, strategy.” Where the successful companies grew was in bottom-line revenue rather than top—shifting their focus, in order to achieve life-bringing growth.

But when growth goes unchecked, it can be devastating. We call it cancer in the body. And before we can prescribe treatment, we must have a diagnosis. Whether we label it a midlife crisis, a corporate denial phase, or an infrastructure problem, we must acknowledge mismatched reality, in order to move forward. Otherwise, misalignment can accelerate decline.

With our imaginary city, it’s a balance between population growth and infrastructure maintenance; with our bodies, it’s a balance between biologic insults and cellular repair; in life, we shift from a growth-heavy childhood to a maintenance-heavy adulthood, including more doctors visits, taxes, and responsibility. It’s this transition from growth to maintenance that creates the S-shape of life, and it’s a delicate balance—easily misunderstood and mismanaged.

It may seem simplistic to minimize the life cycle of so many different topics into only two sides of the same coin. In fact, it is simplistic. While simple sometimes means limited understanding, it also can serve as a practical model for an exceedingly complex world. So take a moment and think: Am I spending too much time in growth phase? What about maintenance? Is this a transition? Where are we?

—

—

Fisher, Marshall, Vishal Gaur, and Herb Kleinberger. “Curing the Addiction to Growth.” Harvard Business Review 95.1 (2017): 66-74. (Source)

Evans, David S. “Tests of Alternative Theories of Firm Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 95.4 (1987): 657-674. (Source)

Importance is the worst thing to put on art, comedy—creativity of any kind. […] If you think this is important, you’re screwed before you write the first word.

Importance is the worst thing to put on art, comedy—creativity of any kind. […] If you think this is important, you’re screwed before you write the first word.

*Disclaimer: The

*Disclaimer: The