Most organizations assume that leadership has to be taught but that everyone knows how to follow. This assumption is based on three faulty premises:

(1) that leaders are more important than followers,

(2) that following is simply doing what you are told to do, and

(3) that followers inevitably draw their energy and aims, even their talent, from the leader.

—Robert Kelly, “In Praise of Followers” (1988)

Life is a balance between doing and observing. Leaders generally preoccupy themselves with the former, while followers tend to err on the side of the latter. But whichever role we find ourselves, both taking action and stopping to listen are required for success. That being said, being a follower is hard work. Despite the common misconception that following is a passive, submissive process, effective following is an active and demanding challenge. In fact, being a good follower is arguably more difficult than being a good leader for at least three reasons:

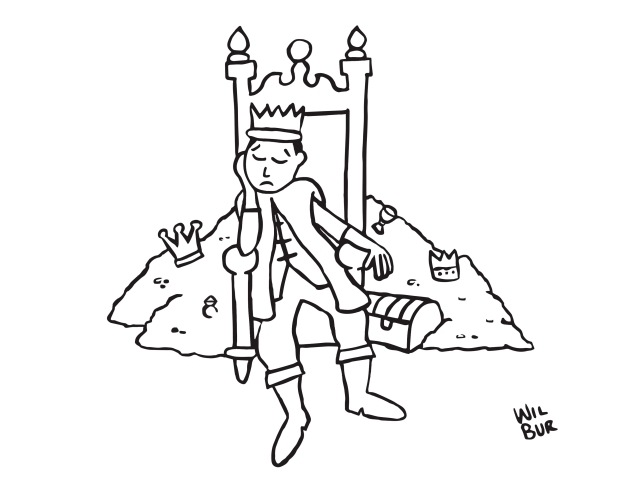

1.) There is far less glory in the role of a follower. Take movie awards for instance: Each year the Academy Awards honors the best and brightest of film with twenty-four categories. An overwhelming emphasis is placed on individual participants—actors, directors, composers. And even second tier awards (categories like “Best Visual Effects”) are received by only a few people representing a team of hundreds. This is not to mention the financial disparity between follower roles like special effect teams and leader roles like individual directors.

Our culture celebrates the individual, the star, the hero, relegating the many hands behind the scenes to tiny, scrolling names after the audience has already left the theatre. However true the phrase, “Behind every great leader you will find a great team,” followers are not adequately recognized for their efforts. We must instead take pride in what was accomplish overall, not the acclaim we received in the process.

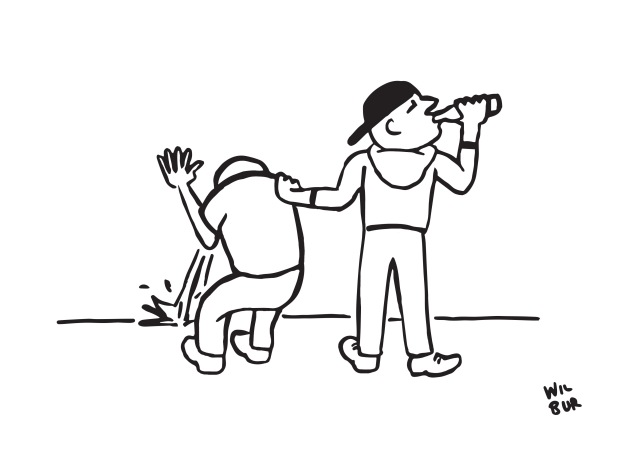

2.) Also, being an effective follower may require more energy than being a leader. In the world of unmanned flight, drone aircraft often fly in groups with one drone leading the rest. These unmanned aerial vehicles expend various amount of fuel (energy) depending on their position within the group. A problem with managing these groups is that follower drones burn more fuel, especially during quick maneuvering, than the aircraft they follow.

Not only do followers have to spend time and energy performing their own duties, they must be constantly monitoring their team and proactively assess what’s next. As followers, we must preempt and adapt to the changes our leaders make. The more influence someone else has on our lives, the more likely our efforts will be duplicated, changed mid-project, or scrapped altogether.

3.) Followers also run the risk of becoming overly dependent. Unlike leaders who often act independently, followers have the dangerous opportunity to abdicate responsibility and opinion. This can lead to unhealthy dependence on outside leadership. Unfortunately, lack of agency can cause feelings of apathy, resentment, powerlessness, and depression, which followers must mange accordingly.

Over-dependence can also leave us directionless in times of change—aimlessly wandering when we are without something to follow. There are times when who or what we follow (be it our children, spouse, career, religious leaders, etc.) disappear suddenly (empty nesters, widows, retirement, scandals, and so on). Some of these drastic changes are inevitable patterns of life, but some changes are unexpected. And whether we’re anticipating a change or taken by surprise, we need to have a plan. We need an opinion and a direction we’d like to take.

Followers must constantly fight the urge to defer our opinions and decisions to whoever’s in charge. Simply due to the nature of the role, it is more difficult as followers to take responsibility and decide the direction of our lives than it is for the leaders who influence them.

—

So why would anyone be a follower? If being a follower provides fewer rewards for our efforts, requires more energy, and puts us at risk of apathy, resentment, and aimlessness, then why would we choose to follow? Why not look to lead instead?

Well for one, we do it for love. We allow our children, our spouses, our desire to change the world outweigh our personal gain. We follow because we must, because there’s no other choice. No person has the capacity to lead every moment of every aspect of his life (nor would it be healthy). And most important, we follow, because when it comes down to it, there’s really no such thing as followers and leaders; there are only arbitrary labels and titles that we assign one another.

Each of us vacillates between following and leading, sometimes switching from one role to the next in an instant. A dirty diaper leads us to the changing table, after which we lead an infant to the park or the grocer or a bike ride. A boss gives us an assignment, in which hours later, we find ourselves “managing up”— guiding them through a proposal.

Every relationship we have, every goal we’re trying to accomplish, is a constant give and take. We must find a balance between totalitarian rule and total apathy, between doing and observing. We may not be the lead dancer at any given moment, but we also cannot go limp—dead weight for our partner to lug around the dance floor. No matter which role we find ourselves—whether leading or following—life is not a passive process.

—

Kelley, Robert E. “In Praise of Followers.” Harvard Business Review. (November 1988) 142-148. (Source 1) (Source 2)

Dubner, Stephen J. “No Hollywood Ending for the Visual-Effects Industry.” Audio podcast. Freakanomics Radio. freakanomics.com, 22 February 2017. (Source)

Choi, Jongug, and Yudan Kim. “Fuel efficient three dimensional controller for leader-follower UAV formation flight.” International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, Seoul, Korea, 2007. (Source)

If trees could read, would they? Or would the fact that books have been printed on mulched up tree guts for centuries be a barrier to literary exploration? And while books may last for years, what would trees think of magazines? As silly as personification is, this line of questioning leads us to the real topic of today’s discussion: If we were like trees, would we live our lives differently?

If trees could read, would they? Or would the fact that books have been printed on mulched up tree guts for centuries be a barrier to literary exploration? And while books may last for years, what would trees think of magazines? As silly as personification is, this line of questioning leads us to the real topic of today’s discussion: If we were like trees, would we live our lives differently?

—

— Importance is the worst thing to put on art, comedy—creativity of any kind. […] If you think this is important, you’re screwed before you write the first word.

Importance is the worst thing to put on art, comedy—creativity of any kind. […] If you think this is important, you’re screwed before you write the first word.

*Disclaimer: The

*Disclaimer: The