Importance is the worst thing to put on art, comedy—creativity of any kind. […] If you think this is important, you’re screwed before you write the first word.

Importance is the worst thing to put on art, comedy—creativity of any kind. […] If you think this is important, you’re screwed before you write the first word.

—Jerry Seinfeld, Comedians In Cars Getting Coffee with Lewis Black

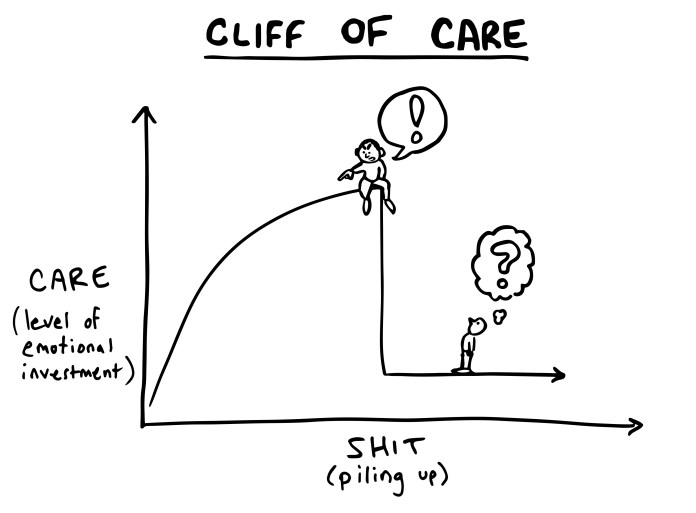

What is the difference between caring too much and not enough? Sometimes it’s just one last straw—one final incident that pushes us over the edge. We see this at our workplaces, contrasting an excited intern with the embattled veteran clocking in and out like a robot. We see it with new parents who trade fashion for durability. And we see it in politics when the news creates such a piercing noise that we simply go deaf to the din.

Like eating or drinking too much, our care has a breaking point. A gluttonous night out can force our stomach from too full to completely empty in an instant, and it is this momentary purge that exemplifies the Cliff of Care. With so many names—outrage fatigue, clarity, burnout, calm, apathy, patience—it can be difficult to know whether the valley beyond the cliff is a safe place to be. As with any journey, it depends on how we got there and our attitude along the way.

Once we reach the cliff’s edge, we can either walk off gracefully, landing softly on the ground below, or get pushed, kicking and screaming, breaking bones on the way down. This is the difference between coming to peace with our situation or becoming apathetic in our resentment. The graceful among us land on their feet through the power of perspective. These are the people who after battling illness, divorce, violence, bankruptcy, discrimination, and many other hardships, still find the positive in each challenge, putting them into perspective. They are calm and kind despite every reason not to be. And they serve as inspiration to “get over” whatever small annoyances we face in life.

Unfortunately, the less gracious cliff jumpers—the ones who bitterly or hopelessly give up the will to care—also exist. Fortunately, the Cliff of Care is not a standalone phenomenon. We may tumble off the cliff and become apathetic to the politics of our world but safely detached at work, no longer wrapping our self-worth in what our boss thinks. This is where awareness can be helpful. Just by knowing about the difference between being on the cliff and being in the valley can help us safely navigate our way.

Detaching emotionally is not something we can will ourselves to do (at least, not immediately). Stepping off the cliff allows us to leave behind our emotional baggage, but first it requires a gradual climb of frustration. This is why telling someone they need to just “get over it” rarely works. Seeing the cliff for what it is can make us come across as callous or cold-hearted when dealing with those who have not yet moved on. Brushing off their emotional concerns as unimportant is seen as dismissive. Rather than pushing them off the cliff to a painful, bitter landing, we must try to remember what it was like to be atop the cliff, empathize, and help guide them down safely.

Conversely, when we’re stranded on the peak of care, pulling our hair out, and wondering why no one else gives a shit, it is difficult to see our position for what it is. We don’t have the perspective. Holding on to what feels important can be blinding. Whether it’s the cleanliness of the kitchen, quarterly sales at work, or death of a loved one, not everyone is going to understand our level of care. And while intense care can motivate us to act, we shouldn’t expect others to follow. When we find ourselves in isolation in a sea of seeming apathy, it may be time for self-reflection. It is immodest to think that we are the only sane people in a world full of crazies.

*Disclaimer: The

*Disclaimer: The

We all have a Confidence Bank Account. Some people seem to have an endless supply of confidence, which buffers them from criticism, mistakes, and failures. Others seem to be forever “in the red,” suffering from self-doubt, low self-esteem, and even depression. But where does this elusive quality come from? How can we earn more of it? And why do some people seem to be immune to the psychologic effects of failure?

We all have a Confidence Bank Account. Some people seem to have an endless supply of confidence, which buffers them from criticism, mistakes, and failures. Others seem to be forever “in the red,” suffering from self-doubt, low self-esteem, and even depression. But where does this elusive quality come from? How can we earn more of it? And why do some people seem to be immune to the psychologic effects of failure?

What is religion? It’s community, history, cultural identity; it’s a way to make sense of the world. Some of us use religion as our primary source of answers; others use mysticism; others: science; and still others use a combination of methods. This is not an argument for one way over the others, but rather a look at beliefs through several different lenses:

What is religion? It’s community, history, cultural identity; it’s a way to make sense of the world. Some of us use religion as our primary source of answers; others use mysticism; others: science; and still others use a combination of methods. This is not an argument for one way over the others, but rather a look at beliefs through several different lenses:

Life is like pouring concrete. (Bear with me here.) The world provides an endless supply of mystery—raw concrete mix—and over time this concrete pours out into our lives, moving from the unknown (concrete mixer) to the known (exposed, wet concrete). We learn new things, have new experiences, and make new discoveries. In this process, we shape our new knowledge into a unique worldview—a concrete foundation. And just like concrete, our worldviews harden over time.

Life is like pouring concrete. (Bear with me here.) The world provides an endless supply of mystery—raw concrete mix—and over time this concrete pours out into our lives, moving from the unknown (concrete mixer) to the known (exposed, wet concrete). We learn new things, have new experiences, and make new discoveries. In this process, we shape our new knowledge into a unique worldview—a concrete foundation. And just like concrete, our worldviews harden over time.