“Community connectedness is not just about warm fuzzy tales of civic triumph. In measurable and well-documented ways, social capital makes an enormous difference in our lives. […] social capital makes us smarter, healthier, safer, richer, and better able to govern a just and stable democracy.”

—Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone (2000)

Imagine this: You look down at your left forearm. There’s a small patch of what looks like dirt. You go to wipe it off, but instead of coming clean, the skin begins to bleed—not a lot, not painfully, but it’s clearly not normal. You try again the next day. It bleeds again. So you stop touching it. A week goes by. Then a month. Then five years. Now the red patch has expanded until your entire forearm is inflamed, bleeding—unrecognizable.

Sounds absurd, right? Why would anyone leave a minor wound to fester for years? And yet people ignore other obvious signs of dysfunction everyday.

I see the equivalent of this in my dental practice all the time: “My gums only bleed when I floss—so I just don’t floss.” And when asked how long it’s been happening, the answer is often: “Oh, I don’t know—a few years, probably.”

Bleeding gums are the dental version of that red patch on your arm: a warning sign we normalize. We tell ourselves it’s fine. We stop poking it. We move on.

But normalized dysfunction is still dysfunction. And bleeding gums are just one example of a much deeper human tendency to discount what we can’t easily see.

It’s why we ignore the quiet decay of underfunded schools in low-income neighborhoods. It’s why people sleeping in doorways become invisible after enough commutes. It’s how overdoses become statistics.

There’s a more dangerous form of collective denial hiding beneath our social systems. Around the world, governments routinely neglect individuals deemed too broken, too complex, or too costly to help. We label them “unrehabbable” or “noncompliant.” We subtly justify abandoning them—socially, economically, even medically.

In political science, there’s a term called “utilitarian distributive justice.” It suggests that government resources should be distributed to maximize society’s overall utility. In fact, it suggests there’s an ethical imperative for such efficiency—an appealing idea when viewed through a cost-benefit lens.

But somewhere along the way, that principle was swallowed whole by market logic. We stopped asking whether society was healthy and started asking whether it was efficient.

We began rationing compassion.

Writing off marginalized populations to “optimize” the majority is like ignoring a gangrenous toe because the rest of the body is functioning. But the body doesn’t work that way. And neither does a society.

This is what I call the Gangrene Effect of public policy: the idea that certain people or problems are too small, too far gone, or too expensive to treat. It’s what happens when we pretend the damage won’t spread.

But gangrene always spreads. What could have been saved with early intervention turns into a full-blown crisis—for the whole body.

Your healthy muscles can’t run a marathon if your lungs are suffocating. You can’t cure cancer or raise children if your appendix has burst. You can’t innovate when you’re hemorrhaging from a wound that everyone pretends isn’t there.

The body acts as a cohesive whole first, and a collection of organ systems second. Society must do the same.

Of course, critics will say, “There’s no such thing as ‘unlimited resources.’ Every body still needs food. It needs rest. It needs to keep moving enough to survive while it heals.” And they’re not wrong.

Priorities matter. But ignoring the damage doesn’t preserve the system—it quietly undermines it.

This isn’t just a policy failure. It’s a psychological blind spot.

Human psychology struggles to acknowledge what it cannot easily see. No one ignores a festering, bleeding forearm in front of them. But it’s easy to dismiss the “occasional” bleeding gums. And even easier—almost expected—to ignore society’s “gangrenous toe.”

Out of sight, out of mind.

But invisible damage is still real damage—seen or unseen, it’s still there. We rationalize dysfunction until it becomes “normal”, until the red, swollen patch has taken over the whole arm—the whole society.

And yes, this entire metaphor rests on a deeper belief: that all of the body — all lives in society — are of equal worth, equal importance, equal necessity. That’s not always easy to accept. But the moment we start ranking whose pain deserves help, we trade society’s health for hierarchy. And hierarchy is not health.

So the next time you read a budget or hear someone dismissed as a “lost cause” or a program cut because it’s “not cost-effective,”

Pause.

Ask: “What would happen if this were a limb on my own body? What if it were my own child? My neighbor? What if it were me?”

And when you hear someone talk about “pulling your weight,” ask yourself: “Which part of the body is choosing to ignore the infection? Which part has the power to act—but doesn’t? Who’s benefitting here? What is this really about?”

This isn’t just about pity. It’s about participation.

People stuck in cycles of poverty, addiction, and violence don’t need our judgment—they need early intervention, investment, and connection. They don’t need to be “fixed” so they can be “productive.” They need to be valued because they’re human. They are part of our body. Part of our community. And we all suffer when they are left to rot.

Gangrene doesn’t stop when we ignore it. It spreads—until there’s nothing left.

“Well, once you have the premise that every human life is of equal value — I mean, that directs a lot of what you do — both your money and your efforts, and the people you attract, and all sorts of things involved in that.”

— Warren Buffett, Inside Bill’s Brain: Decoding Bill Gates, Part 2 (2019)

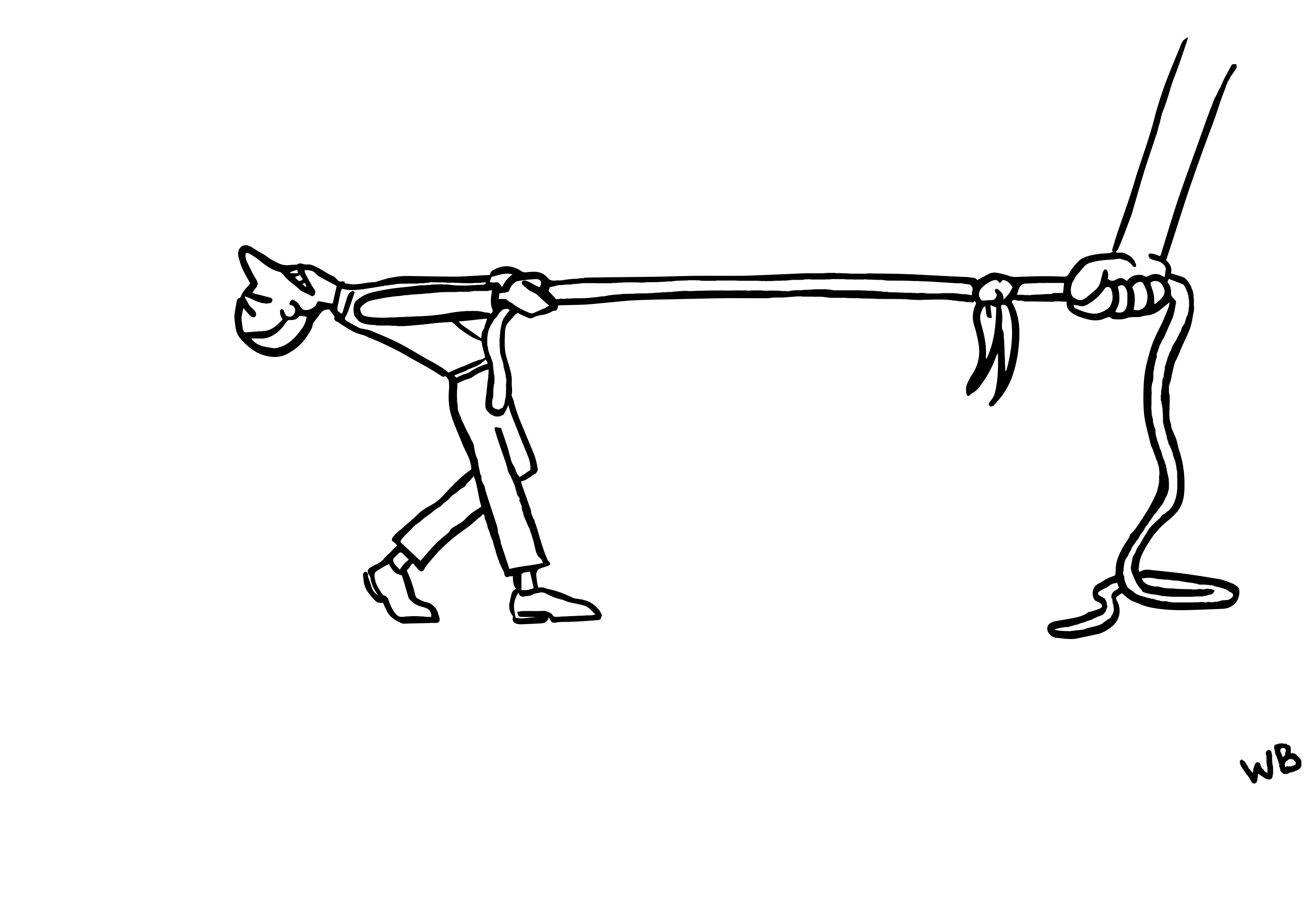

What’s do you see? What comes to mind when looking at the image above? Is it a celebration of the modern woman’s accomplishments—breaking down gender barriers while juggling life’s many tasks? Or perhaps it’s an example of

What’s do you see? What comes to mind when looking at the image above? Is it a celebration of the modern woman’s accomplishments—breaking down gender barriers while juggling life’s many tasks? Or perhaps it’s an example of